We know that creating a positive transition into a private rental can turn those feelings of hesitation and doubt into emotions of excitement and empowerment for a young person who is still establishing their independence.

Specialist Homelessness Services (SHS) support young people to carve out a way for a young person to find stable employment, create relationships, provide shelter and deal with complexed trauma. While SHS services provide this vital role, the real estate sector plays the most crucial role in young people accessing and being successful in a private rental property.

Real estate engagement has been a taboo topic for several years in the SHS sector. With only a handful of successful one-off funded projects of this nature, delivered in a specific location across NSW and even fewer nationally, there was a proven need for a boarder and more consistent approach.

Even with the introduction of private rental subsidies such as Rent Choice Youth and rental guarantee’s, both available through NSW state government initiatives, barriers around the stigma of homelessness from agents remained a constant response. The issues around perceived stigma have been long felt by the SHS sector when trying to place a young person into stable and secure housing. Along with the reality young people are more likely to have a lack of rental history, which further contributes to the challenge of finding a private rental. In 2018 the NSW premier advised a priority of reducing youth homelessness by 2019. Increasing access to the private rental market was a key strategy under this priority. Yfoundations saw this as an opportunity for cross-sector collaboration and proposed the pilot concepts of the NSW wide, Foot in the Door initiative.

Development and design of Foot in the Door

To understand the barriers young people and services were facing in accessing private rental opportunities, Yfoundations consulted further with SHS members and the broader sector to obtain an understanding of how we could improve young people accessing the private rental market. Simultaneously Yfoundations was working closely with the Real Estate industry to understand the challenges they faced with considering young people for private rentals. Yfoundations received feedback around a lack of rental history and affordability as the significant barriers to accessing a property. Issues of stigma were prevalent from Real Estate agents but more so towards those young people who were currently residing in a shelter, refuge or transitional housing. Some other barriers expressed equally by both SHS service workers and the Real Estate sector were the challenges of maintaining positive relationships with high staff turn over and communications, highlighted by statements like,

“ We used to be able to get many clients into properties when John was at the agency, but since he left it’s like starting all over again every time with someone new, they don’t know what we do, and we just don’t have time to start over continuously.”

The critical considerations for the Foot in the Door initiative were to develop a consistent approach to Real Estate engagement with the potential to be scaled across the state and easily adapted or duplicated nationally.

The Foot in the Door was then designed to:

- Increase agent’s knowledge on the roles and function of Youth Homelessness Services

- Provide an introduction to property managers in understanding trauma and youth homelessness

These aims would foster increased communication and relationship building between SHS and the real estate sector. Creating accessibility and uptake of the Rent Choice youth subsidy and improved access to the private rental market for those young people leaving SHS services for which it was suitable.

When reflecting on the learnings of existing work done across NSW we were able to see that the most common way the community sector has sought participation from Real Estate agents was through networking breakfasts in the hopes of building one on one relations.

When designing the Foot in the Door model, taking the elements of what was working well was necessary, however, considerations of the projects ability to be saleable, evaluated and duplicated were vital.

One of the early pieces of feedback in initial consultations with the Real Estate Industry was the need for the SHS sector to speak the same language as the Real estate agents. The first learning in this was something straightforward, in defining our audience; we quickly learnt we needed to be speaking to property managers and not in fact Real Estate Agents as so much of our work had previously referred to. Foot in the Door also had to produce content that could be delivered and relevant to any location across NSW, and simple enough to be understood by even Real Estate administration staff. Key partners for the Real Estate industry also provided input into the development of a potential delivery model. The Real Estate Institute of NSW being instrumental in the core piece of work focusing on training and skills. A secondary element would see a communication strategy created to promote relationships and information share.

What is Foot In The Door

Foot in the Door is a face to face training program that provides up to date information and resources highlighting key focus area’s in language Real-Estate Agents can relate to.

The key topic areas of learning in the program for agents introduce agents to the challenges of youth homelessness. Exploring the financial and social impacts on young people and the broader community. This element was an important part of developing the ‘what’s in it for me’ for agents.

We realised that many agents didn’t have even a basic understanding of the role of the SHS services, so the possible benefits of working collaboratively with services was not within conception.

Resource videos of lived experience case stories, including genuine agent recommendations were created to demonstrate this highlighting the client, worker, agent relationships working cohesively to support new and existing tenants.

From an ethical perspective, it was important to include some introductory understandings around trauma practice, adapting the content to be trauma-informed leading to trauma informed tenancy management. This outlined theories on trauma triggers and understanding isolated incident, ongoing and vicarious trauma as most relevant for agents. It was hoped that with this knowledge agents could adopt a varied approach to daily interactions with tenants and potentially influence their workplace practice.

Knowledge about available Government Subsides Rent Choice Youth and tenancy guarantees was high on the topics of interest for property managers and this worked in favour when opening the conversation of potentially suitable properties to be offered for lease in promotion of new tenancies for SHS leavers. Property managers were also provided a short workbook with some details of the services available in their local area.

Delivery

Delivery of Foot in the Door was done across a number of platforms.

Face-to-Face: training sessions were two-and-a-half hours each at five locations across NSW, Sydney, Liverpool, Orange, Port Macquarie and Armidale. Training was hosted in community or Government spaces, with morning/afternoon tea provided to encourage networking.

Webinar: Online delivery was hosted by REINSW with promotion and registrations being carried out through their database of agents and stakeholders.

Roadshow events: Annual CPD training events conducted by REINSW were an ideal opportunity to network with local agents and provided a wide reach for information dissemination.

Events: Significant events held within the Real Estate industry were important to develop the visibility of Foot in the Door concept. This included being an exhibitor Australian Property Management Expo with over 700 property managers in attendance.

Evaluations

This first stage evaluation focused on the relevance, concepts and delivery of the program to property managers, and the potential short-term outcomes of the of the work. The key questions the evaluation aimed to explore were: Are real estate agents satisfied with the Foot in the Door training? Does the Foot in the Door training contribute to changes in real estate agents’ knowledge and attitudes relating to homeless young people?

Property managers that participated in the training were firstly asked a series of questions to establish a baseline attitudinal scale. Secondly post training the same questions was asked along with reflections on training content and knowledge gained. The results outlined the biggest affect was an agent’s likelihood to connect with services after participating in Foot in the Door training. The evaluation also specified participation rates, 150 people attended Foot in the Door training: 43 face-to-face; and 107 through webinar. A further 118 Property Managers were reached through direct contact with the REINSW Roadshow events.

Overall participant satisfaction with the Foot in the Door program was high. The webinar retention rate was 100%; and face-to-face training achieved a net Promoter Score of 64. Post training feedback provided reflected that on average, Foot in the Door significantly improved attendee’s understanding and competency around youth homelessness.

The majority of Real Estate Industry attendees reported improvement in:

- knowledge about youth homelessness (58%)

- knowledge about trauma (50%)

- ability to recognise behaviour associated with trauma (50%)

- confidence to connect a tenant with a youth worker (75%)

- knowledge of the subsidies and supports available to young tenants (67%)

Foot in the Door has achieved outcomes beyond what was expected in a short period of time: young people were connected with private rental opportunities; and Property Managers implemented new practices to support young tenants. Further opportunities to improve young people’s access to private rental tenancies were also identified through this pilot.

The Future of Foot in the Door

The outcomes realised through the project went beyond the boundaries of evaluation questions alone, as relationships with the property sector were built at every level and extended to introductions that saw larger new build developers with offers of available properties. With new knowledge of SHS systems, agent’s came to understand the majority of young people make consistent payments to reside in a SHS services, with majority of agents suggesting that a statement proving these payments included with a new tenancy application could possibly be viewed similarly as a rental ledger, somewhat solving this issue. This work also highlighted pockets of opportunity for the development of future work for Yfoundations. We witnessed, SHS engagement with private business, leading to conversations around improvements and engagement with temporary accommodation providers working towards better outcomes for clients, particularly relevant in regional areas. Another area for future exploration for Foot in the Door will look into the development of a broader tenant referral systems aimed at direct property management referral to SHS services. This initiative will identify at risk tenancies for early intervention long before young people are facing evictions or even presenting at services.

The future Foot in the Door program sees property managers and caseworkers working side by side in a co-supporting relationship with common goals and a deep understanding of the challenges being faced by all parties. This can only be done by continuing the availability of this training to the property sector and providing the platform to have impactful conversations with stakeholders such as REINSW. It is inevitable that through this process we will evoke long-term systemic change accoss the wider sector.

Foot in the Door challenges both the property sector and services to work in a truly progressive way and realise common goals and benefits that may not have been apparent until recently. At no other time in history could it be more accurately said “we are all in this together”.

A copy of the full evaluation report from 2019 is available at the Yfoundations website. For more information on the Foot In The Door program please contact Lauren Brown: lauren@yfoundations.org.au

]]>Nicole and her family had been living in her rented home in the Shoalhaven for three years when she got an eviction notice. The house had a serious mould problem that Nicole had been asking the real estate to look at for some time without success.

“This house and its mould problem was making my family sick.” Nicole told me, “My daughter has asthma, and the mould really affected her. My son who is a toddler was getting sick every few weeks. I got really sick. All of this was connected to the mould—it’s a very serious issue.”

When Nicole followed up on the repairs for the property with a new property agent at the firm she was told they would talk to the owner. Instead six days later she got given a ‘no grounds’ eviction notice (that is, an eviction with no reason provided).

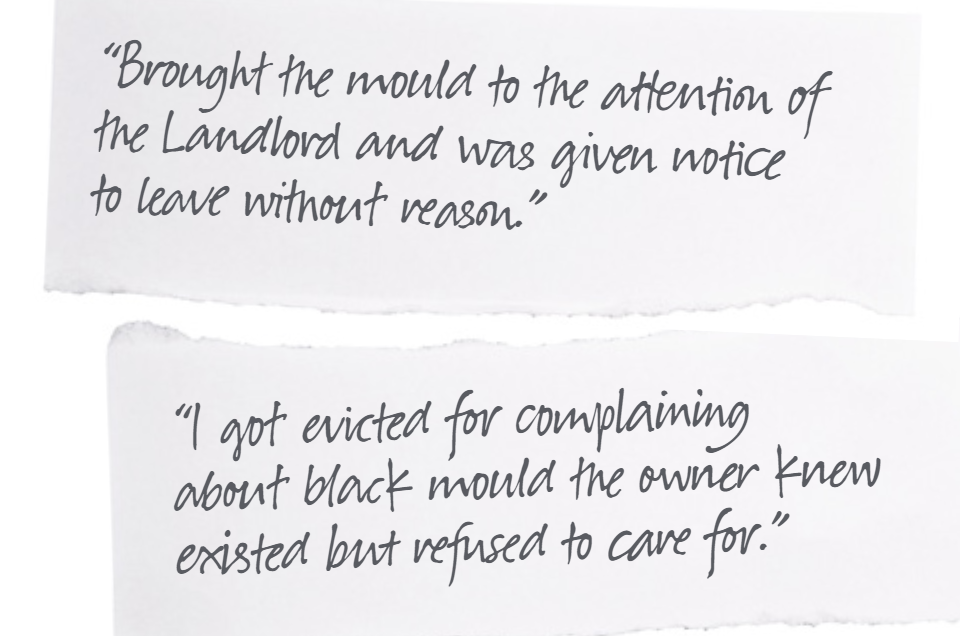

Sadly Nicole’s story is not an isolated one. Serious mould infestations in rental properties because of a landlord’s failure to conduct necessary repairs are unfortunately also common. Recently renters shared their experiences of mould and renting with the Tenants’ Union for submission to the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Health, Aged Care, and Sport’s recently announced inquiry into biotoxin-related illnesses in Australia. We received more than 100 formal responses from across the country within 48 hours, and they continued to come in at the same volume over the next few days. These included stories of retaliatory evictions for chasing mould repairs along similar lines to Nicole’s experience. Some quick examples:

Mould is a serious health issue. Renters should be able to confidently request repairs to a rental property that will eliminate mould in their homes and ensure the health and safety of their household. But it is clear that tenancy laws in NSW and indeed around the country do not adequately protect renters who assert their rights. Chase repairs and next thing you know you find yourself evicted.

But this is not only about mould. At the Tenants’ Union of NSW, and across the nation-wide network of state-based tenants’ advice services, we talk to tenants every day who report being evicted in retaliation for asserting their rights. These include asking for repairs, looking to negotiate regarding a rent increase, and requesting the landlord give them notice before knocking at their door. Sometimes because of discrimination, or simply a relationship breakdown, their landlord says—or doesn’t say—they just ‘don’t like them’. The result is the same: a lack of action on pressing issues, or a no grounds eviction.

Realities of renting

The landscape of renting has changed—renting no longer fits (if it ever did) with the stereotypical imagined ‘student sharehouse’ or as a stepping stone or transitional ‘phase’ for young people before moving on to purchase a home. In NSW almost a third of all households rent their homes. Those of us renting are doing so for longer and often with kids. A third of all those in the private rental market are classified as ‘long-term renters’—that is, we’ve been renting continuously for ten years or more. A growing number of us recognise we’ll likely be renting for life.

Although there are some advantages to renting, the reality is that people who rent their homes in the private market do not experience the same levels of stability and comfort. Rents are rising and are quickly becoming less affordable. For those on low incomes they have long been unaffordable. Renters move home much more often than people who own their home. One in three renters are likely to have moved home in the last year, and more still (around 40%) have moved three or more times in the past five years. Last year when Choice, National Shelter, and the National Association of Tenant Organisations undertook a survey of renters they found:

- Almost a quarter of all renters reported ongoing problems with pests, doors or windows that didn’t close properly, peeling paint and loose tiles;

- Half reported having been discriminated against;

- One in seven tenants said they held back from asking for repairs because they were afraid of a rent hike or getting evicted; and

- Around one in ten said they had been evicted for ‘no reason’ at least once since renting.

We need to Make Renting Fair

Clearly tenancy laws have not kept up. They do not offer the protections required to ensure liveable, secure, affordable homes for renters.

It is now almost three years since the NSW Government began a statutory review of the Residential Tenancies Act 2010 to determine whether the law was working effectively and reflects the needs of the community. After a short period of public consultation at the end of 2015, a Report on the Statutory Review was tabled in Parliament mid 2016. Disappointingly the Report did not pick up on a number of the key issues flagged by the many tenants, tenant advocates, and community and consumer organisations who actively took part in the Review’s consultation process. In particular, the Report made clear that the review would not address the need to remove provisions within current tenancy law that allow unfair (no grounds) evictions. The Victorian Parliament has now passed the ‘RentFair’ bill.

Enter #MakeRentingFair. The community campaign—launched last year in June—is backed by a strong coalition of around 100 organisations made up of a mix of community and faith-based organisations, tenants groups and tenant advocates, consumer rights groups, and unions. At the end of last year Inner West Council endorsed the campaign, followed by Randwick City Council earlier this year. The campaign focuses on the issue of unfair (no grounds) evictions. Currently a person who rents their home in NSW can be evicted without being given a reason. Sections 84 and 85 of the NSW Residential Tenancies Act 2010 allow a landlord to issue what is called a ‘no grounds’ eviction notice at the end of a fixed term lease or once the lease is outside of a fixed term. The Tenants’ Union estimate that of the over two million people who rent in NSW, at least 160,000 will experience a ‘no grounds’ eviction while renting.

Unlike grounds for eviction that exist during the fixed term period of a tenancy, such as breach of agreement or sale of premises, tenants can’t dispute the reason for eviction if they are given one, except in very limited circumstances. This means renters have very little protection in the face of retaliatory or discriminatory evictions.

Since we launched the campaign, many people have shared stories about their experiences of receiving a ‘no grounds’ notice. We’ve heard from people evicted for chasing much needed repairs—things like fencing around pools, and significant mould issues; or questioning why their rent increase was so high; or asking the landlord to give them notice when they were coming to the property. Renters have told us consistently that instead of being an incentive for a tenant to comply with their responsibilities, the threat of eviction has a chilling effect on their confidence to assert their rights as renters.

What has the campaign achieved?

The campaign has made good progress in the year since we launched. We have a strong supporter base—both in terms of the coalition of organisations who publicly endorse us as well as the growing number of individual supporters engaging with the campaign. We’ve had excellent media coverage of the issue with renters’ stories about the impact of unfair (no grounds) evictions appearing regularly in the news and helping to build community understanding about the level of insecurity renters face and how ‘no grounds’ evictions undermine the other rights renters have. Significantly we have also seen the NSW Greens and NSW Labor come out strongly on this issue. Both parties have adopted a strong renters rights policy platforms that include removal of unfair ‘no grounds’ eviction as a priority reform. Luke Foley, leader of the NSW opposition, has publicly committed a NSW Labor Government to ending unfair evictions, most recently when speaking at a Renters’ Rights Assembly out the front of Parliament House at the end of June.

Last year the Better Regulation Minister, Matt Kean, conceded ‘no grounds’ evictions were a problem, stating in October: “No-grounds evictions, retaliatory evictions, all these things are currently undermining renters’ rights in NSW.” However the NSW Government continues to avoid dealing with the issue, confirming that they will not be removing ‘no grounds’ provisions when they finally do announce the tenancy reforms coming out of the review of the Act.

Meanwhile, other Governments are improving their Residential Tenancy Acts. The ACT currently has a 26 week notice period for ‘no grounds’ evictions – though unfortunately the longer notice period is not as effective a disincentive against use (and misuse) that you might hope it would be. The ACT Government has made a number of reforms to its RTA in the last 18 months, and a second tranche of reforms is expected to be introduced to the ACT Legislative Assembly in October.

In Victoria, the Government has recently introduced to the parliament of Victoria amendments to its RTA, commonly known as the “RentFair” bill. This legislation requires rental properties to meet minimum health, safety, and energy efficiency standards. Mould will be treated as a priority maintenance issue, and locks, heating, and insulation will be covered. Tenants will have a right to make minor modifications, including anchoring furniture to improve child safety, and the onus will be on landlords to object to tenants having a pet, rather than the other way around. Significantly, the reforms will require that landlords provide a reason when they end a tenancy agreement by removing the 120 day ‘no specific reason’ notice to vacate from the RTA, and only allow the use of an ‘end of fixed term’ agreement at the end of a tenant’s first fixed term. This is a great step forward towards ending unfair evictions.

In June the NSW Parliament unanimously confirmed housing as a human right and recognised their responsibility for providing safe, secure, and affordable housing. Despite this, it seems the NSW Government will miss this valuable opportunity to implement reform that would bring significant improvements to security and stability for people who rent their home.

]]>In housing strong regulation of banks (including public ownership of banks), land release policies and preferential policies for home buyers all contributed to a high rate of home ownership (the most secure form of tenure) and low rate of private renting (the least secure). In employment, a formal commitment to full employment and centralized wage fixing gave workers, especially those with less bargaining power, a bigger say. In both areas, most of those policies have been dismantled.

The last 30 years have seen a dramatic increase in ‘non-standard’ forms of employment. This includes part-time jobs, and casual and contract employment. There are some real advantages to these changes for many – they allow workers to combine work and other commitments (like caring for family), and can mean more control over the work we do. But there is growing evidence that for many these changes just mean less security and less bargaining power.

The days of full employment have long since gone. Australia’s unemployment rate barely rose above two per cent for the three decades following WWII, it has barely fallen below five per cent since. Underemployment is also on the rise; more and more of those with a job want more hours than they are offered. And because jobs are more ‘flexible’, they are also less stable, meaning we often cannot be sure if we will still have a job in six months’ time. When you combine these trends with falling union membership it is hardly surprising that wages are barely growing, despite steady economic growth. Flat wage growth is now one of the major drivers of rising inequality.

We are now witnessing an increase in the ‘gig economy’, where workers are employed on a very short term basis. The typical examples are the rise of Uber to replace taxi drivers, and of Airtasker to source all sorts of jobs from ‘handy person’ work to editing and graphic design. A similar trend has emerged in housing as well – through AirBnB. Because all of these examples use the internet to change the way we do things, the gig economy is often linked to debates around automation, and the potential for automation to significantly reduce the number of jobs.

The gig economy and automation, however, are distinct trends. As Jim Stanford from the Centre for Future Work has argued, in most gig jobs new technology plays a relatively minor role, focused largely on connecting buyers and sellers. The handy person does much the same thing they did before. The Uber driver still drives a car to pick you up and drop you off. The service itself is almost identical – what has changed is the way we connect workers and consumers. This is quite different to changes in manufacturing, where the nature of the work itself has changed dramatically as computers and robots replace people.

So why are gig jobs growing so quickly if they involve so little change? One explanation is that these online platforms circumvent the rules we have developed to regulate labour and housing markets. Airtasker workers and Uber drivers are legally independent contractors (although this is increasingly being challenged). They pay all their own overheads and have to manage all their own cash flow. If you are only doing this on the side for a bit of spare cash, that’s fine, but if it replaces more stable jobs, then it is a problem.

So what does all this have to do with housing? Well it is driving some of the growing inequalities and insecurities we see in the housing market. As more and more people work in less stable jobs – either on short-term contracts, or as casuals or in the ‘gig’ economy – so they can find it harder to access stable housing. First, without a stable job it is difficult to get a mortgage, which means you cannot buy a house. Australia now has one of the highest household debt to GDP ratios in the world, driven almost entirely by mortgage debt. And unlike most other similar countries, debt is still rising after the financial crisis. Expensive housing and high debt make insecure work a much bigger problem.

Insecure work is just as much a problem for renters. If your income fluctuates every week then you are forced to manage your finances much more actively to ensure you can cover the rent in periods where you have fewer hours or no work. Low paid and underemployed workers are more likely to have insecure forms of employment, and also have less of a financial buffer when things get tight. It is not surprising this leads to a growing number of people scarifying essentials to pay the rent. The new world of insecure employment is also creating problems for the other policies we have to help those in need. Many government payments are highly targeted – meaning only those on low incomes get help, and that support is withdrawn as you start to earn income. This creates two big problems. Often working an extra shift leaves you with not much extra cash, because benefits are withdrawn at much higher rates than apply for taxation. Second, it can be hard to predict what you will earn, and government systems are often slow in responding. This can mean you lose benefits based on previous earnings just as you lose shifts – leaving you with no money, or even a debt.

For those in social housing, the problems are potentially even worse. Because governments have invested so little in social housing, while the demand for social housing has been growing, access is now very tightly targeted. Indeed, the main way governments have used to ‘reduce’ public housing waiting lists has been to make it harder to get on the list, not to provide more housing. As a consequence, only those on very low incomes generally qualify. If you are in social housing and you start to earn more, then you risk losing your home.

The strong eligibility rules are less important in a world of stable full-time jobs. If you get a new full-time job it will pay a reasonable wage and you know it will be fairly stable, so you can afford to move into other forms of housing. But in the new world of insecure work you might get a good contract and then find yourself without enough income soon after. If you lose your house in the process – forcing you into a much more expensive and less secure private rental market – then that is a huge loss. So big a loss, in fact, that many tenants might avoid initially taking work (especially if it is short-term, casual or contract). Ideally, those small ‘gigs’ would give people experience and connections to get more work. But our social housing system is not designed for the new world of work.

The problems of integrating ‘targeted’ social housing and insecure work are so bad that governments have been forced to try new things. One of the reasons for new models of housing for key workers is precisely this problem. The state government has been exploring other options too – it knows it is a problem – but the whole structure of housing provision is so deeply based on targeting it often ends up making things worse.

None of this is to argue that we can or should return to the pre-reform days of the 1960s. But the combination of changes in employment and housing are proving unfair and unsustainable. A gig economy of short term contracts might be feasible if people were guaranteed secure and affordable housing as a right. Strong targeting of social housing can make sense in a world of secure full time jobs. Taken together, however, insecure employment reinforces the worst aspects of our expensive and insecure housing system. For now, the fight for more secure work and a fairer housing system are bound together.

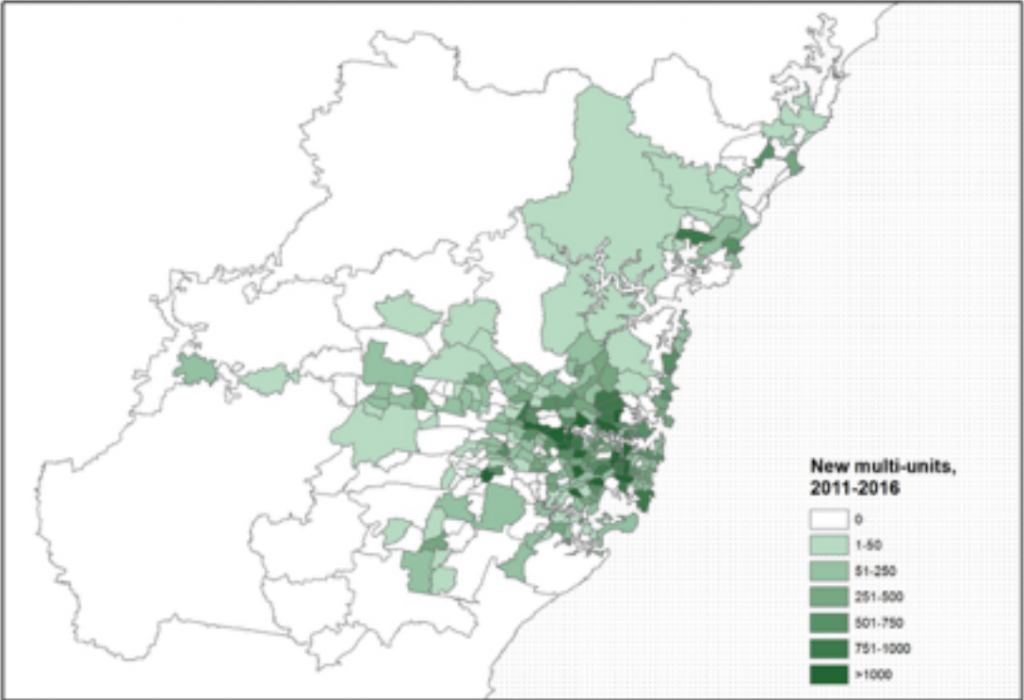

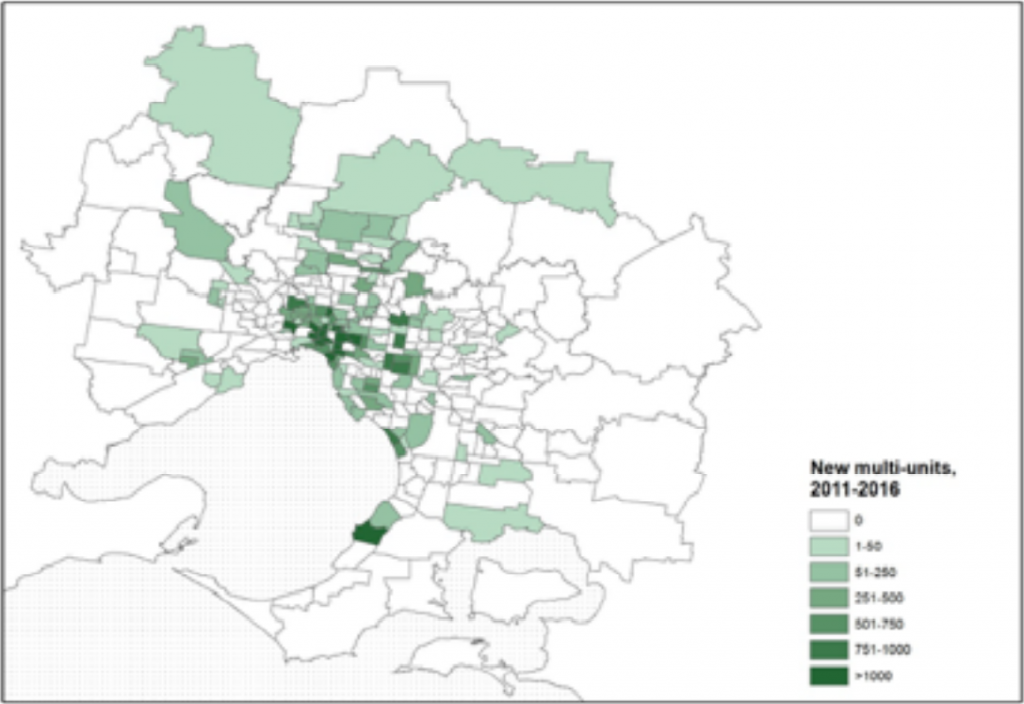

]]>There is obvious truth in the claims that housing choice and diversity have indeed widened in the last few decades as a result. The tatistics clearly show a much greater spread of dwelling options in our cities – with apartments now accounting for 28 per cent of all homes in Sydney and 15 per cent in Melbourne. As the accompanying maps show, while the bulk of recent growth in the apartment stock in Melbourne and Sydney are clearly in and around the inner city, even the more distant suburbs have witnessed an increase in higher density residential development.

For many, the opportunity for urban living in inner city location is clearly a preferred choice for the stage in their life when apartment living in an upcoming and ’vibrant’ neighbourhood is a real attraction. High density urban renewal has been a boon for hipsters and students alike.

But the issue of choice really needs to be unpacked carefully. For many others, the “swing to urban living” is more a necessity than a positive choice. True, the surge in apartment building has put a large number of properties onto the market to rent or to buy that are clearly cheaper than houses in the same suburb. From that point of view, they have added to the relative affordability of living in these neighbourhoods. However, affordable to whom is an open question – $850,000 and upwards for a standard two bedder in Waterloo, South Sydney, and $500,000 or more in Melbourne’s Docklands for a similar property, and rent levels to match, are not exactly a cheap option for anyone on a low income.

But other than in the prestige areas, where higher income down-sizers and pied a terre owners can be enticed to buy in some comfort, much of what is being built is straightforward “investor grade product” – flats built to attract the burgeoning investment market. It can be argued that the investor has always been a major target of apartment developers, even in the 1960s and 1970s when strata units became common, particularly in Sydney. But it is even more so today.

Despite the clamour to control overseas investors perceived to be flooding into the country, the bulk of investors in the apartment market are home grown. We don’t need to rehearse the debates on the factors that have fuelled this splurge, but clearly, the development industry has been savvy to the possibilities of this market. In the last decade, backed by state planning authorities and politicians desperate to claim they have ‘solved’ housing affordability by letting apartment building rip, developers have moved into this market on an unprecedented scale. The figures bear this out: for the first time, Australia recently built more apartments that houses, and the majority end up for rent.

In the rush, we, the housing consumers, have been offered a motley range of new housing with a series of escalating problems to address. Leaving aside the issue of amateur management by owners’ bodies in charge of multi-million dollar assets, problems of short-term holiday lettings and neighbour disputes that turn sour, there are more serious concerns over build quality, defective materials and fire compliance. A history of deregulation of the building industry – moves toward complying development approval for high rise, self-certification of building components, complex design and non-traditional building methods, relaxation of defect rectification requirements, long chains of sub-contractors, poor oversight by local planners and authorities, and cheap or non-compliant fittings and finishes, plus the rush to get buildings up and sold off, has left the apartment market wide open for poor quality outcomes. Not to mention the fly-bynight ‘phoenix’ developers who vanish as soon as the last flat is occupied, never to be found when the defects bill come in. The lack of consumer protection in this market is astounding – even the average toaster comes with more consumer protection – at least you can get your money back if the product fails!

These particular chickens will surely come home to roost in lower end of the market that will never attract the wealthy empty nesters or cashed-up professionals with the resources to maintain their buildings in good order. In Melbourne, space and design standards, including windowless bedrooms, have come under critical scrutiny, as has site cramming, with tall apartment blocks cheek-by-jowl in overdeveloped inner- city precincts. At least NSW has State Environment Planning Policy 65, which provides guidelines for space and amenity standards, and the BASIX environmental standard, prevent the more egregious practices.

But the problems of density are likely to be most felt in the many thousands of new units now adorning precincts around suburban rail stations and town centres, built under the uncertain logic of ‘transport orientated development’, often replacing light industrial or secondary commercial development. They attract a mixed community of lower income renters, many from recently arrived immigrant groups, and marginal home buyers – often first timers. Many have young children – the only option for young families to buy or rent in otherwise unaffordable housing markets. Overall, though, renters predominate.

What will be the trajectory of these blocks, once the immediate gloss wears off and those who can move on do so? You only have to look at the previous generation of suburban walk-up blocks in these areas to find the answer. Far from bastions of gentrification, the large multi-unit apartment building in lower value locations will drift inexorably into the lower reaches of the private rental market – if they are not already there. Town centres like Liverpool, Fairfield, Auburn, Bankstown and Blacktown in Sydney point the way. Indeed, the cracks in the density juggernaut are already showing in many of the more recently built blocks in these areas – literally, in many cases.

The inexorable logic of the market will create suburban concentrations of lower income households on a scale hitherto only experienced in the legacy inner city high-rise public housing estates. With the latter being systematically cleared away, the formation of vertical slums of the future owned by the massed ranks of unaccountable and profit-driven investor landlords is a racing certainty. The consequences are all too easy to imagine.

The call for greater regulation of apartment planning, design and construction is now being heard in some quarters – as the 2015 NSW Independent Review of the Building Professionals Act highlighted.1 But don’t hold your breath for rapid progress. No one wants to kill the goose that’s laying so many golden eggs for the development industry and government alike – especially in inflated stamp duty receipts. The market has a habit of self-regulating on supply, of course, and the current evidence of a marked downturn in apartment building is a clear sign of that. But don’t expect the market to self-regulate on quality, at least with the current highly fragmented, confusing (not least to builders and bureaucrats), under-resourced and largely unpoliced regulatory system that is supposed to oversee such development. The legacy of this entirely avoidable crisis is completely predictable, but will be for future generations to pick up.

]]>Rising complaints about tourists in residential apartments and homes prompted a NSW Parliamentary Inquiry into the Adequacy of Regulation of short Term Holiday Letting (1). Since the Inquiry concluded in mid 2016, Sydney’s Airbnb listings alone have grown from around 15,648 in January 2016 (2), to reach a total of 24,038 homes by April 2017 (3). Over approximately the same time, 24,469 new apartments were completed in Sydney (4). These figures are not connected, but highlight the changing ways that homes are being designed, financed and used in high density urban and suburban settings.

The proliferation of online holiday rentals in particular have not been planned for, as highlighted by the NSW Parliamentary report which found current planning regulations “fragmented and confusing”. Short term rental accommodation is not defined under NSW planning legislation, and the legality of a range of “home-sharing” practices now enabled by online platforms such as Airbnb remains unclear.

In addition to traditional short term holiday lettings (whole dwellings which are solely reserved for holiday accommodation), online platforms allow the listing of primary residences when occupants themselves are travelling, as well as rooms, and shared rooms.

The permanent or frequent letting of whole homes is regarded to be most problematic, but holiday rentals have long operated in coastal towns and in tourism regions, typically without the need for special planning approval. The sudden appearance of tourists in urban and suburban buildings and neighbourhoods, particularly in inner Sydney and Melbourne, has attracted

particular public attention.

Echoing concerns in high density cities of Europe and North America, residents complain that tourists generate increased noise, rubbish, traffic and parking congestion and are prone to loud and drunken behaviour. There is also wider disquiet about the increasing presence of visitors, an intangible transformation of local neighbourhoods. This impalpable change— described by some scholars as tourist-driven gentrification, arises when permanent homes are converted and residents displaced by holiday accommodation.

The conversion of permanent rental housing supply to short term accommodation has been endemic in New York, London, Berlin, Barcelona, San Francisco and Vancouver. In these cities governments have cracked down heavily on Airbnb and other online platforms to prevent affordable and rent controlled units in particular from being used for holiday accommodation. We don’t have nearly as much affordable housing to protect in Sydney, although the sell off and subsequent listing on Airbnb of former public housing in Millers Point was particularly poignant.

Our own analysis shows that general pressure on already tight rental vacancy rates in high demand suburbs of inner Sydney will be exacerbated if online holiday listings of whole homes continue to grow (5). Our study found that in central Sydney frequently available Airbnb homes amount to around one and a half times the rental vacancy rate (the proportion of rentals available for local households to rent at any one time), and nearly four times the number of rental vacancies in the Waverly Council area, which includes Bondi.

In a city trying to beat its affordability crisis by building new supply, it seems counterproductive to be leaking existing or new housing stock into the holiday rental market. But rather than launch a New York style crack down, the NSW Government has opted to tread lightly for now. The NSW Government’s long awaited response to the Parliamentary Inquiry has promised “broad consultation” involving industry and the community. This consultation, supported by an “options paper” will identify “appropriate regulations” that enable the sector to “continue to flourish and innovate whilst ensuring the amenity and safety of users and the wider community are protected”.

It appears likely that the “options” will involve amendments to planning laws to clarify that principle residences can be rented for up to a specified number of days without the need for further planning approval, and that short-term letting of rooms where hosts remain present will also be permitted. Short term letting of empty houses (i.e. homes which would otherwise be vacant) may also be permitted with no or minimal need for planning approval, subject to “impact thresholds”.

The main shift in the Government’s position appears to be recognition that strata communities need more tools to manage short term rental accommodation in all its forms. The cautious approach may also reflect the fact that internationally, attempts to regulate online holiday rentals have had limited success. Despite New York’s ban on short term holiday rentals, which now extends to the advertisement of these properties, Airbnb listings in that city have continued to grow.

However, in some cities, and usually following legal action, Airbnb has agreed to help implement local rules, for instance, by collecting and remitting applicable tourist taxes, or by blocking bookings once a threshold is reached. Such an arrangement has been introduced in London, where Airbnb has established a “day counter” which automatically restricts bookings beyond a 90 day calendar year threshold, unless the host has obtained planning permission to operate a holiday rental property.

It is too early to know whether this action will operate to curb London’s growing conversion of permanent rental accommodation to tourist accommodation or simply result in landlords turning to other online platforms (such as homefromhome.co.uk), but the intervention represents an important first step.

The NSW Parliamentary Inquiry and Government response also anticipate greater use of voluntary and industry codes of practice as well as market based forms of regulation (for instance, where users rate each other). Airbnb itself is piloting a “Friendly Building Program” in the US, where owners’ corporations are able to take a percentage of income from Airbnb bookings and set specific policies (such as blackout dates).

Market based regulations and voluntary codes may be feasible in a sector which is highly conscious of branding and public image. The NSW Government’s default position appears to rely on existing local government powers to act in relation to noise or other complaints, while potentially empowering strata communities to set and enforce their own rules.

However, these individualized and market-based approaches may undermine strategic planning strategies designed to cluster tourist accommodation near facilities, services, and attractions. Nor do such approaches address the potential impacts of short-term rentals on the availability and cost of permanent rental housing. The NSW Government hasn’t said much about housing affordability, promising only to monitor the issue with reference to national visitor survey data which record accommodation trends.

In a country and city gripped by a crisis in affordable housing supply, the omission of any concrete commitment to defend permanent rental housing from conversion to holiday accommodation, and indeed to protect renters themselves from sudden eviction, at least in high demand urban locations in and around Sydney, is a key concern. It would seem that regulators in NSW and many other states in Australia are out of sync with their international counterparts, who have made a clear distinction between

home sharing and the loss of rental supply from their permanent rental

markets.

Sydney had the glitz and glamour, but now had high culture and a decent football team (AFL of course), great food, good nightlife, new horizons. Sydney felt right, but my Sydney didn’t really extend beyond Ashfield to the west, North Sydney to the north, the airport to the south and all the way east to the ocean. I am a bit of a snob when I define my Sydney. It’s viewed through a lens from a different time. When I lived there the bulk of the lower-priced rental was actually in the inner city. This has, of course, changed, and low and moderate income households don’t rent—or live—where they used to.

I left Sydney in 2002. We could never afford home purchase, my parents were ageing and we figured we’d seen Sydney at its best. Fifteen years in midlife was great but how would the rest pan out? Overall the move has been good, we’ve paid off a house we now own, have good friends, we now have grandchildren that add extra spice. Would that have been possible if we’d stayed in Sydney?

True the humidity of Brisbane and those extra few degrees sometimes get to me and the food and culture up here improves without reaching that international standard, so every time I fly in to that big bold beautiful city that Sydney is, my heart still skips a beat as I take in the glorious vistas and I wonder… Then I realise we were paying $250 per week for a two-bedroom shop top flat in the heart of Enmore. While not flash it was well located; while noisy it had 50 restaurants within 200 metres, public transport on tap and a gastro pub across the road. It had room for our cat and even a small plot of backyard and a part of a garage. What would it cost now?

Well, based on our recent Rental Affordability Index (RAI), we would need a household income of $150,000 per year for the rent in that area to be moderately affordable, and that would mean the rent for our old flat would be about $800 per week. Sydney has become ridiculous.

This RAI showed what we all thought wasn’t possible, that rental affordability in Sydney has deteriorated further. All renters on average sit right on a threshold. The entire city, accounting for the incomes of all renters and the prices of current rents, is effectively unaffordable. You really need to be earning over $150,000 a year as a household to rent a two bedroom flat at anything like an affordable level. Even then you must pitch outside what I think of as Sydney. Not till you reach Canterbury, Parramatta, or Epping does it get affordable even with a household income of $150,000.

The average household income in Australia is around $85,000 per year. At that income only postage stamp areas in the Blue Mountains and beyond Richmond show affordable three bedroom rentals. Parts of Liverpool and on that radius are affordable for two bedroom properties, but we are into two hour commute country.

For pensioner couples trapped in the rental market virtually nothing in NSW is affordable to rent. They will be paying up to 65 per cent of their income to secure rental dwellings. Sydney is not alone in this regard, but fares the worst among our capital cities.

The RAI this year introduces some new features to our interactive map. The overall average data shows how close to the affordability threshold all dwellings in Sydney and many parts of NSW are, but the real story of rental affordability only comes out when one plays with income levels, household configurations and when you look over time.

The map is still being made freely available for public use and it’s a great tool that demonstrates rental affordability for any area we have data and that includes all of NSW.

Interestingly, Hobart is the second least affordable capital city. This is due to lower income levels relative to rents in Tasmania. After that Brisbane and Adelaide have moderate affordability, while Melbourne has the best rental affordability of all east coast capitals. Perth has been improving but just to reinforce the point, no capital city in Australia has any rental housing that is affordable for pensioners, low income working households and many, many others.

I have been using the RAI, especially the interactive map, to look at the Productivity Commission’s (PCs) recent Inquiry Into Human Services, specifically the social housing part of this report. The PC recommends (among other things) increasing CRA by 15 per cent for the most disadvantaged, supplemented by a similar payment from states. That amounts to about a $10 per week increase in CRA for a pensioner or pensioner couple.

A pensioner couple has an income of $45,000 per year, and this would lift that income by $520. Even if their income was added to by an additional $4,500 per year, bringing it to $50,000 (and more than doubling CRA), this would not lift them out of rental stress in Sydney.

Renters in the rest of NSW do not fare much better. For people with an income of $50,000 per annum most of the coastline in NSW remains unaffordable. Affordability wise, Coffs Harbour and the north coast look like Sydney. At $70,000 per year areas around Newcastle and Nowra and regional areas even on the coast become affordable but as we all know, peoples’ incomes in these areas are lower than those in Sydney.

This is a crucial point: affordability is relative to peoples’ capacity to pay. Some regional cities and towns (parts of the north coast are a case in point) have high rental costs in absolute terms. But even in areas where rents are lower, if the majority of the workforce is employed in, say, the service sector, even relatively modest rents will be unaffordable. The RAI is a new tool. At National Shelter we use it to raise the profile of rental housing affordability in the media. But it has also become a tool that people can utilize to look at affordability in their own area. Use the link, play with the variables and see what stories you can tell with it. I am going to use it to model the PC inquiry recommendations and take snapshot maps to show how little $10 a week will help in Australia’s rental market.

People make a lot of sacrifices to live in Sydney but the current rental market means more than sacrifices, it means genuine hardship, poverty and exclusion. People do without medicine, without food, without petrol, can’t register their car, pay insurance or fix broken appliances. The relative cost of rents, especially in Sydney, now generates real poverty and homelessness. This tool doesn’t fix that, but it does illustrate it. And getting that message through is vitally important.

]]>